Stones

“It’s rare to meet the most complete expression of poverty,so an idea for a picture came to me on the spot. I made an appointment with them at my studio for the next day” Courbet wrote in a letter to Francis Wey about the moment he saw the two men.

In ‘Gustave Courbet, His Life and Art’ (1972) Jack Lindsay writes ; “he posed the two models separately. The old man , Gagey, had spent his whole life on the roads around Ornans and was a well known character. The painting was much admired by local folk, who, according to Proudhon, proposed to buy and hang it over the altar in the parish church, as it pointed so strong a moral, that was no doubt a tale told him by Courbet. And in a later fragment; “His remarks during the work on the canvas to Wey and Champfleury show that he particularly felt his emotion because of the way in which the working-together of the old man and the youth expressed the cycle of unending misery that the system around him perpetuated. He was not painting two workers doing a specially backbreaking job and getting a poor reward for it, but the whole endless repetition of hopeless toil among large sections of his people, the whole endless cycle of exploitation. The strength and fullness with which he felt the nature of the image was determined by the movement to socialism which was going on inside him”. This fragment clearly shows that Lindsay writes from a Marxist art -theoretical perspective.

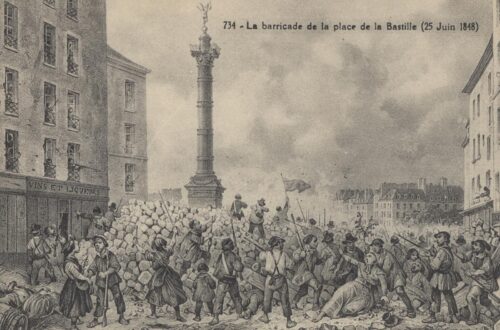

According to Michelle Facos; stonebreakers were peasants forced off the land into backbreaking and poorly compensated wage labor, the benefits of which went directly to the middle and upper classes. Because of this, Courbet’s stonebreakers did not represent an ideal image of the rural peasantry to contemporary viewers. Significantly Courbet did not idealize these stonebreakers, they wear dirty, tattered and mended clothing. These strong and oppressed workers who spent their day hacking apart stones, seemed threatening to contemporary, middle class viewers in 1850, the year stonebreakers debuted at the Salon. While the majority of 1848 revolutionaries were urban craftsmen and workers Courbet’s stonebreakers instilled fear because they wielded implements that were potential weapons and produced the paving stones used for barricades and projectiles by revolutionary insurgents

Courbet encouraged a feeling of mistrust by shielding the men’s faces from the viewer. Because their expressions and physiognomies could not be read, viewers could not determine whether these men were dangerous or submissive. Courbet painted an image that provoked anxiety in a destabilized and modernizing world”.

TJ Clark describes this feeling of unease; “(…)if people and bourgeois were true allies, then the People must be represented- and the bourgeois was going to find himself in their midst, one against four, or one against hundred, a colonial planter surrounded by slaves.”

The final version of ‘the Stone Breakers’ didn’t survive the second World War and was destroyed when a transport of paintings from the Dresden Gemäldegalerie to Königstein Castle was bombarded by American war planes. Purely by associating I had to think about Kurt Vonegut’s book ‘Slaughterhouse five, or a children’s crusade’. In it Vonnegut describes his own experience as a prisoner of war, and the senseless destruction of Dresden, in the only possible way he saw fit. His main character Billy Pilgrim seems to travel through time and space, human years do not seem to matter and chronology is in a total mix up. Billy seems to float from sphere to sphere, his total acceptance and the way Vonnegut describes everything in a clinical way makes reading the book an intense experience.

Still from the movie ‘Slaughterhouse 5 or a Children’s Crusade’, 1972, director George Roy Hill. ( Music score by Glenn Gould!)

“Many holes were dug at once. Nobody knew yet what there was to find. Most holes came to nothing- to pavement, or to boulders so huge they would not move. There was no machinery. Not even horses or mules or oxen could cross the moonscape. And Billy and the Maori and others helping them with their particular hole came at last to a membrane of timbers laced over rocks which had wedged together to form an accidental dome. They made a hole in the membrane. There was darkness and space under there. A German soldier with a flashlight went down into the darkness, was gone a long time. When he finally came back, he told a superior on the rim of the hole that there were dozens of bodies down there. They were sitting on benches. They were unmarked. So it goes. The superior said that the opening in the membrane should be enlarged, and that a ladder should be put in the hole, so the bodies could be carried out. Thus began the first corpse mine of Dresden.”

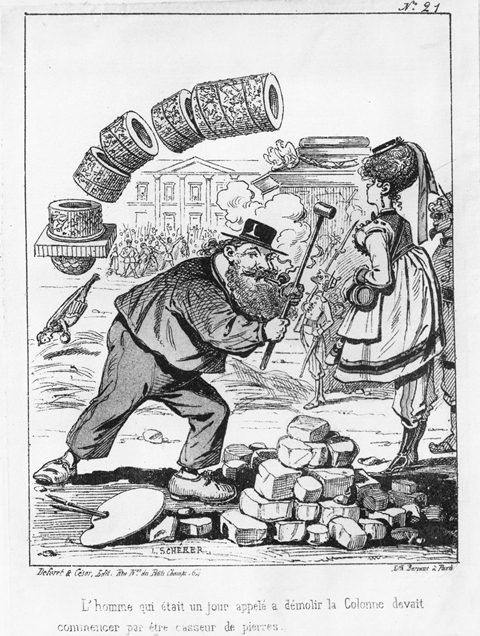

Because of his role in the Paris Commune Courbet was imprisoned and later held personally accountable for the destruction of the Colonne Vendôme. He was sentenced to pay a sum of ten thousand francs a year to pay for its reconstruction.

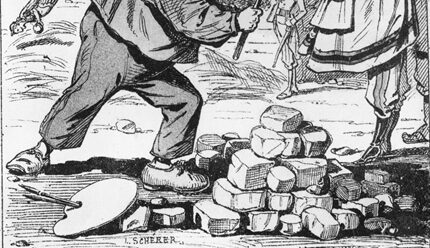

In this caricature by Schérer Courbet is pictured as a convict, the text reads; “The man who was called to demolish the Column might just as well start working as a stonebreaker”

The conviction and trouble to bring in the 10.000 Francs a year was so oppressive that Courbet decided to flee to Switserland in 1873, where he died on the 31st of december 1877.

According to historian Pierre Chessex Courbet’s family wanted to bury him in Ornans; “but on Monday Dr Blondon of Besancon, the fiancee of Courbet’s sister Juliette, bought a concession in the morgue of the cemetry of La Tour- de -Peilz.” From 1878 until 1919 Courbet’s body rested in a double coffin of oak and lead in the morgue. Today one can find, hidden between a couple of shrubs, a plaquette marking the location of Courbet’s temporary grave. Body and tombstone were moved to Ornans in 1919. What I find striking when I look at the two photographs is the fact that while the grave in La Tour-de Peilz was covered in ivy, the Ornans grave is covered with gravel!

Sources;

‘Gustave Courbet, His Life and Art’ (1972) Jack Lindsay, Jupiter-London 1977,

‘An introduction to 19th century art’, Michelle Facos , Tailor & Francis Ltd, 2011,

‘The Absolute Bourgeois, Artists and Politics in France 1848-185’, T.J.Clark, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973. Slaughterhouse 5, or the Children’s crusade; A Duty-Dance with Death, Kurt Vonnegut, Vintage UK , 2000

https://france3-regions.blog.francetvinfo.fr/vallee-de-la-loue/2016/01/03/ils-sont-venus-sur-la-tombe-de-courbet.html